Safety Decisions - April 2018

By: Charles J. Douros

Printable Version

EHS Daily Advisor - December 2017

Printable Version

Time. It's the one commodity we can agree is always in short supply. Or is it? Perhaps it's just what we do with the time we're given that creates the perception it is escaping us. After all, we all have the same 24 hours in any given day. Managed well, time can pave the way to greatness, allowing us to produce immensely powerful, positive outcomes. Squandered, it often lends itself to disastrous and disappointing results.

Safety professionals know all too well how valuable time is. There is constant pull in every direction. There's never enough time spent "on the floor" or "in the field." Company reports and regulatory documents take hours of office time, interrupted by countless emergencies we are called to manage. Many safety professionals are independent contributors working tirelessly without staff, and others have only part-time direct reports. If you're fortunate to have a dedicated staff of safety professionals, managing their time is paramount to freeing up discretionary time for yourself. This discretionary time can be devoted to high-value projects, strategic thinking and personal or professional development. Frankly, you can do with it what you want, not what is being dictated or demanded by others.

Consider this: your employees steal discretionary time from you every time they interact with you. When you address them, you are diverting your own time and attention away from that which you would rather be doing. Where do the employees fall in your organization? Are they stealing inordinate amounts of your discretionary time, or are you managing them in such a way that wasted time is kept to a minimum?

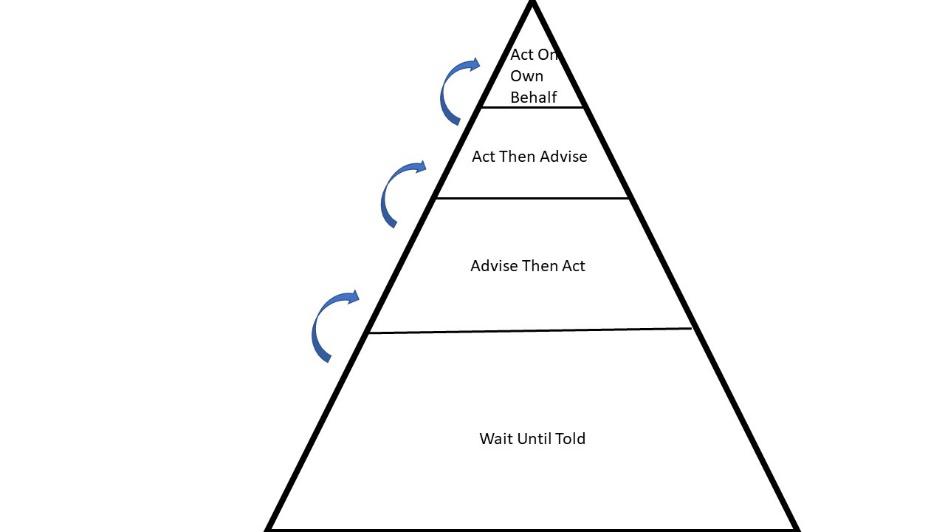

Adapted from Bill Onken's model on time management, all employees can be placed in one of four tiers in a time management scale.

Wait Until Told

Those who reside in this largest block will steal the greatest amount of your discretionary time. These employees won't lift a finger until you direct them to do so. You are so busy tending to their needs, you don't have time for your own. A new employee fresh out of orientation is an example of someone who waits until told. Another example is an employee who sees a large puddle of water on the factory floor but does nothing to remedy it until he's told to mop it up. The hazard will remain until he is directed to address it. The sooner you can help this employee rise up the scale, the more discretionary time you will find.

Advise, Then Act

This next group of employees in the continuum first advise what it is they intend to do, then wait for approval or instruction before taking any action. They take a bit less discretionary time to manage. While it's a step in the right direction, these employees still steal too much discretionary time from supervisors and managers. In the example where the employee sees water on the floor, this employee would seek a supervisor and notify them that there is water on the floor and then advise them on how they intend to clean it up. The supervisor then takes time to evaluate the proposed solution and gives authority to continue, or direction on completing the task.

Act, Then Advise

Further up the scale, and providing maximum value relative to discretionary time, there is a smaller universe of valuable employees who take initiative to act on the hazards they encounter then communicate their actions to you at a later time. "Hey boss, I saw a large puddle on the factory floor and I put up wet floor signs, told the area supervisor, called the sanitation department and waited there, diverting foot traffic until they came." It takes a more mature organization with high trust levels to endorse this mindset among employees. When employees take the initiative to act then advise, it takes very little time to address them: only as much time as it takes to listen and thank them for their efforts.

Act On Own Behalf

In most organizations, few employees reach the point where they are accountable only to themselves. Those who can act on their own behalf go about their business confidently, making observations, assessments and good decisions regularly, with great acumen and without hesitation. These employees make organizational change happen and don't seek approval, permission or recognition for doing so. Their impact may or may not be immediately evident, and improvements are often subtle. It is a pleasure to manage these individuals since they consume none of your discretionary time at all.

Where do the lion's share of employees fit in your organization? Are they mostly in the "Wait Until Told" bucket, stealing hours of discretionary time from your day? Are you actively working on helping them promote up the scale to "Advise Then Act?" Are the trust levels in your organization high enough to set expectations for more employees to "Act Then Advise?" What steps can you take to create a culture where more individuals are acting on their own behalf? If you're struggling to find enough time in the workday to accomplish more of what you want, and less of what they want, assess your organization and answer these questions. It'll be time well spent.

For more information, call +1.936.273.8700 or email info@ProActSafety.com